Bounty Land file in the Case of Louis Devau alias Innocent Mathieu, Veteran of the War of 1812 who fought at the Battle of New Orleans January 8, 1815

A few days ago, I received information requested from the National Archives in Washington DC about bounty land warrants for my 3rd generation great-grandfather, Innocent Mathieu (Mathew) also known as Louis Devau, a veteran of the War of 1812.

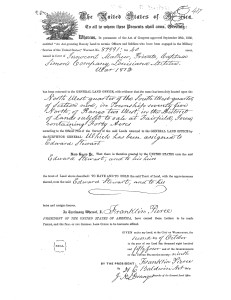

Included in Innocent Mathieu’s bounty land file is a document which indicates a land warrant No. 87991 was issued in accordance with the act of September 28, 1850.

Since this was my first look into the application process for bounty land, I needed to learn more about how veteran land warrants and patents worked, and under what authority they were issued.

Bounty land warrants (BLW’s) were originally authorized by the Continental Congress in 1776 as an inducement to enter and remain in military service, but later acts of Congress authorized them as a reward for past service. BLWs provide the right to free land in the public domain. The warrant was a piece of paper which states that, based on his service, the veteran is entitled to X number of acres in one of the bounty land districts set up for veterans of the War of 1812. These land districts were located on public domain lands in Arkansas, Illinois, and Missouri.

A veteran who decided to redeem his warrant was issued a patent for the land itself, and a bounty land warrant file was created in the General Land Office. This file contains the surrendered warrant, a letter of assignment (if he assigned his interest to another party), and any other documents pertaining to the transaction. The warrant itself should include the name of the veteran, his rank on discharge, his branch of service (including company), and the date the warrant was issued. It may also include the date the land was located and a description of the land. For more on Bounty-Land and Warrant for Military Service 1775-1855 see here.

Warrant No. 87991 for 40 Acres issued in Favor of Innocent Mathieu, Private in Captian Simon’s company, Louisiana Militia, War 1812. However shows Land Patent is assigned to Edward Stewart and his heirs.

Once I gained a better understanding of what this file was supposed to include, I continued my search and found a document within the file indicating that Innocent Mathieu received a bounty land warrant no. 87991 on May 13, 1853, for 40 acres for his service in the Louisiana Militia during the War of 1812 (the Battle of New Orleans, Dec. 1814 – Mar. 1815).

The death record found in same file, indicated that Innocent Mathieu (Mathew) died on April 13, 1845. Yet, as noted above, a bounty land warrant No. 87991 was issued to Innocent Mathieu on May 13, 1853. Also, a bounty land patent (title to the land) for 40 acres was issued on Oct 2, 1854 and assigned to a gentleman named Edward Stewart and his heirs.

A veteran of the War of 1812 was issued a land warrant eight years after his death, and another man, not the qualified veteran nor his family member, was granted the land patent. (Double click photo to enlarge)

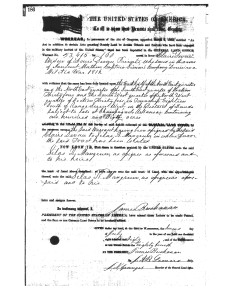

Another document in this file indicates that the veteran’s widow received a land patent for 160 acres, under warrant No 53415, on Nov 3, 1855, in accordance with an act of March 3, 1855. She is identified as Claire Devau, widow of Louis Devau, a private who served as Innocent Mathieu under Captian Simon, Louisiana Militia, War of 1812. However, it was also documented in this file that no record application under the act of 1855 was on register (referencing Warrant no 53415).

I looked up Act of 1855 and discovered that on March 3, 1855 (10 Stat. 701), the U.S. Congress went beyond merely satisfying the former pledge of the Continental Congress and authorized the issuance of bounty-land warrants for 160 acres to soldiers, irrespective of rank, who had served for as few as 14 days in the Revolution or had taken part in any battle. Widows and minor children of such veterans were also eligible. An individual who had received a warrant under previous bounty-land legislation was limited by the act to receiving a second warrant for only such additional acreage as would total 160 acres. To see more about bounty land file and warrants see here

Another document indicated that the veteran’s widow received a land patent without having an application on file. How could this have happened?

Warrant No. 53415 for 160 Acres issued in favor of Claire Devau widow of Louis Devau, Private who served in the name of Innocent Mathieu, in Captian Simon’s company, Louisiana Militia, War 1812. However shows Land Patent is assigned to Silas R. Mangrum and his heirs.

In the case of the 160 acres under warrant 53415, a bounty land patent on July 2, 1860 was assigned to a Silas R. Mangrum and his heirs. However, the two bounty land warrents were set aside and granted to Innocent Mathieu. Yet, no record application under the act of 1855 was on register (referencing Warrant no 53415).

Puzzled by these findings, I now wish to know how the land, amounting to 200 acres, ended up in the hands of two unknown men and their heirs.

Was this land stolen from the widow and family of a dead veteran of the War of 1812? Was fraud involved in any of the application processes? Is there any evidence in the form of documentation that could prove such assumptions? What became of this land? These are just a few questions that came to mind as I summarized my initial review of the bounty land warrant file of Innocent Mathieu.

Stay tuned as I reveal more evidence discovered in this case of the bounty land promised to Innocent Mathieu, a veteran of the War of 1812 at the Battle of New Orleans.

See more here: Deep Roots

Michael, “stolen” would make a far more interesting story, but that was not likely to be the case. By the time these bounty-land acts were passed in 1853 and 1855 to benefit volunteers in the War of 1812 (i.e., men who had not qualified under the bounty land acts passed during the war itself for the benefit of men who enlisted for the duration of the war), these men were aging. Taking on the task of clearing raw land, which might not even be available anywhere near their home, was something that many of the old volunteers and their widows did not feel feasible. They simply sold their warrant. To quote archivists Eales & Kvasnicka’s intro to the subject of bounty land in GUIDE TO GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES, 181: “Nearly all these warrants were assigned [to someone else] and the assignees [those who bought the warrants] used the warrants as payment or partial payment for tracts of land on the public domain.” The purchasers were often land speculators. Many acquired hundreds or thousands of these warrants and then consolidated them into a mammoth tract of timberland in places such as the upper reaches of Minnesota.

Elizabeth, Thank you for your comment, Indeed “stolen” would make for a more interesting story and while I am still looking into this particular case of Bounty Land set aside for my veteran ancestor of the War of 1812, I can’t help but think, that something other than a proper transaction took place which led to 200 acres of land ending up in the possession of someone other than the intended recipient.

So far, there are two documents in bounty land files of the person in question. One document has the word fraudulent applications written across and in another document, a statement was written in a letter which says, “Judge who signed application is about to be remove for office”. Just these two piece of evidence found in my ancestor’s file has me more curious about the persons involved, than the actually property possibly stolen now.

I came across an article written by A. B. Pruitt titled Military Bounty Land Warrant and the Glassgow Land Fraud, see here that article: http://www.tngenweb.org/tnland/pruitt3.htm and wondered, if there were others incidents which may help me to better understand how prevalent this practice was for both veterans of the American Revolution and possibly the War of 1812 which in the case of my ancestor.

In a letter which states the removal of the Judge who signed application, the author cite about 10 to 15 applications by number which were pending or awaiting approval that, he had not heard back about from the office bounty land warrants. This may require me to research each of them, in order to determine the name of the Judge in question stated to be removed.

Indeed the plot, mystery continues and so does my research.